Perhaps one of the most remarkable qualities of the Flinders Island literature that I have been exploring over the last week is, simply, that most of the people who write it are visitors. That is, by far and large, the written work produced about Flinders Island and the surrounding Bass Strait islands is done by people who are only in the area for a short time. The greatest surprise is that this even extends to the non-fiction and guide books! (Indeed, of the four readily available guide books for the island, only one is written by people who live permanently on the island.*)

This is not necessarily a criticism of the quality of the literature of course. To imply this would imply that all travel writing is inferior, that all temporary residencies are creatively stunted, and that my own time on Flinders Island cannot produce anything of value! Actually, quite the reverse is true, since some of the best commentaries are written by visitors precisely because they are able to offer some perspective. Even so, the temporary nature of the authors of Flinders Island literature is, nevertheless, worthy of note.

And with that introduction, I present to you a very local poet: Elvie Bowman.

Bowman’s work, published in a booklet (I assume on Flinders Island, although no date or publishing details are given), is a collection of the poetry that she put in the local newsletter. The sweet foreword summarises the contents nicely:

A collection of poems written by local poet Elvie Bowman.

For many years Elvie’s poems have appeared in the “Island News” and have usually been written on topical subjects.

They express her feelings and vast knowledge of the Island, the people, and the animals in it.

Bowman’s poetry is well-known, and was invariably the first (sometimes only) answer I received to the question of what literature about Flinders Island is written by an islander. That marvellous blog Island Life Style; references Bowman’s most famous work, a sea shanty style poem written in the 1970s, “Where the Roaring Forties Blow” (in the booklet called simply “Flinders Island”). While I am not intending here to offer a full explication of the poems, I’d like to draw out a few points from Bowman’s work, to get an idea of what constitutes her unique voice.

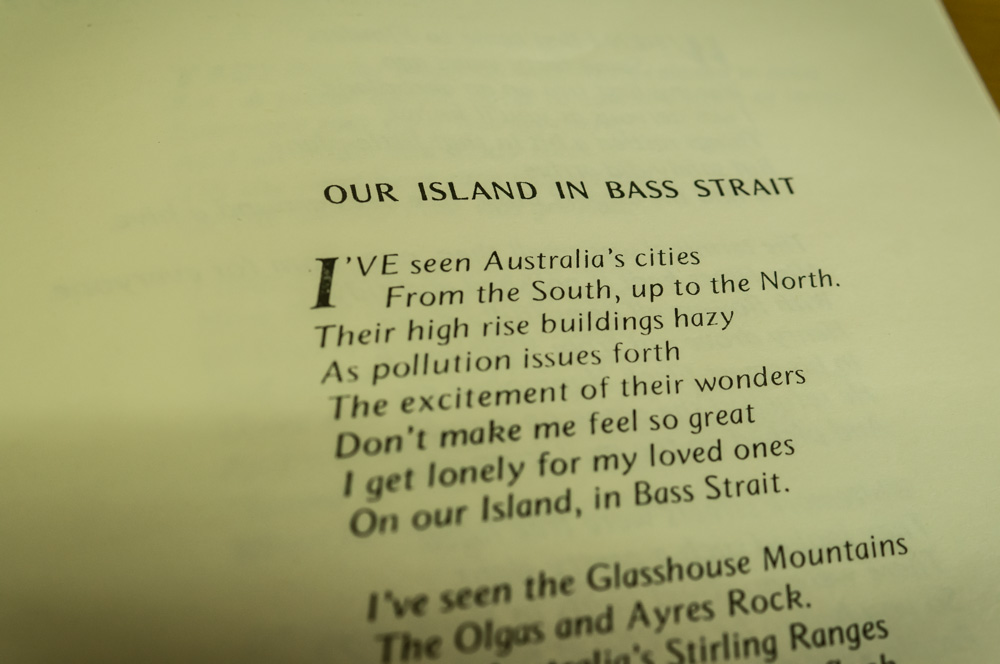

Most obviously, the poems follow a traditional form: stanzas with end rhymes, and a great many of Bowman’s poems are rhyming quatrains (abcb). This form suits the theme of the poetry, since Bowman in many ways offers an island form of pastoral poetry. Her verses describe the everyday rural life of the islanders, with some celebrations of the idyll. This form also has the advantage that it feels like poetry – it draws attention to its own recognisable and repeating patterns, and is very familiar for most Anglophone readers.

This conservative form is then filled with an appropriately familiar use of language. The lines are from everyday life, and colloquial phrases give the poems a local character. In her poem “Pros and Cons”, Bowman says “Our cattle though are something” (4.1), and then later adds that the bull “doesn’t do things by halves” (5.4), the familiar idioms making for a very relaxed reading. The rhythm of the poems is also colloquial, often using “but” when desiring to clarify or expand on a statement, and there are a few rhetorical questions so open ended that punctuation marks aren’t even used (“Tell me, where does a dollar go” (7.4), “But what’s the use of grumbling” (12.1)). The language is inclusive, tending to be unambiguous even when using idioms, and very few poetic devices (similes, metaphors etc) are used. As such the poetry is quite self-contained, making very little reference to things beyond the island, and when these do occur they are comfortably familiar. In “Pros and Cons”, Bowman describes the island sheep through invocation of the nursery rhyme Baa Baa Black Sheep: “They all yield their three bags full” (2.3).

This tendency to focus on the island extends to a suspicion of non-islanders. In “Michael Middleton Esquire”, the vet fondly remembered as an impostor when he was newly arrived on the island.

From mainland Halls of learning came

A man, in neat attire.

He brought a piece of paper,

Should anyone enquire.

His name was written on it,

In Ink still slightly wet,

Announcing to us common herd,

This man, is ‘Mick da Vet’

The poem describes the vet’s early mistakes, when he was accidentally taking the lives of dogs and cats, and thus proving right the islanders’ suspicion of the outsider. Even so, Mick finds his place on the island, improving his veterinary ability but also proving himself as a person to the community as a singer, musician and dancer. As he settles into island life, the Islanders in turn accept him, and the poem ends “Should someone ask “who is that Man”/They are told, that’s ‘Mick da Vet’”, transforming the derogatory title into an in-joke that Mick is a part of.

This non-islander “other” is best demonstrated through the use of Bowman’s anonymous “they”, which turns up in several poems. In “Our Fading P.O. Tower”, the eponymous tower is being pulled down. “Now ‘they say’ it isn’t needed” the poet informs us, referring skeptically to this unknown authority that deems the tower no longer necessary. The poet, conversely, will miss the tower, and unlike the nameless authority she bestows human traits on others who will miss it, including golfers, boaters and birds.

These descriptions of island life are evocative precisely because they are recognisable and local. The simple language becomes a vehicle for emotions and events because it does not draw attention to itself. In “The Drought 1987/88”, the line “The sheep so weak and cattle so thin/With calves at foot and no milk within” does not attempt to dress the animals with anthropomorphism, or to describe their suffering with emotive language. Instead, Bowman allows the events to be evaluated for what they are: hard facts of life.

While some of Bowman’s rhymes and metres are a bit forced, she is nevertheless able to offer a poetical form of island life. The famous Flinders Island wave *can* be over-analysed, to amusing effect, but the wave is ultimately just a familiar and distinctive islander form of communication. In much the same way, Bowman’s poetry could be dressier, drawing on more intertextual references and poetic devices, but it would be less distinctively representative of the island. As such, Bowman’s poetry is a demonstration of a particularly local sense of the island, and a local expression of it.

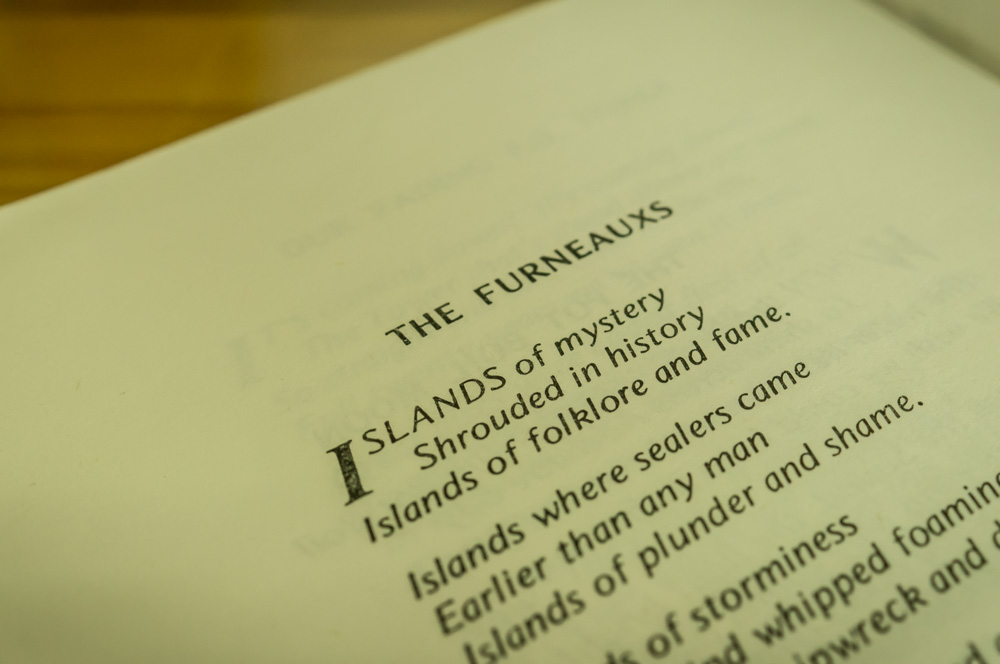

Other Island poets include Don Napier and Derek Smith. Derek Smith’s “The Song of the Furneaux Islands”, which also illustrates many of the same properties as Elvie Bowman’s work, appears in Jean Edgecomb’s book Flinders Island and Eastern Bass Strait.

We live on a beautiful island

Set in a sapphire sea

Relying on one another

And living in harmony.

From the beaches of Palana

To Strzelecki’s lofty peak

It’s a beautiful, beautiful island

With peace for all who seek.

We see the wildflowers growing,

Hear song birds in the trees

And watch the boats unloading

Their harvest of the seas.

The cry of our wild geese echoes

O’er the tidal stream

And muttonbirds slowly circle

As silently as a dream.

When freezing gales of winter

Roar through the sheoak trees,

There’s a wild, majestic splendour

In the clouds and the raging seas.

And as we all grow older,

Still prouder we will be

Of our beautiful Furneaux Islands

Home to you and me.

*Of the guide books available in Bowman’s General Store (Whitemark), which accounts – as far as I can tell – for basically all the guidebooks readily available, a good half is written by seasonal or occasional visitors. “A Walking Guide to Flinders Island and Cape Barren Island”, now in its third edition thanks to Dooreen H. Lovegrove and Steve Summers, is printed by the Flinders Council, and has always been a product of islanders. Ken Martin of “Walks of Flinders Island” draws on an extensive and personal knowledge of the island, having spent seasons on it bushwalking for the last 30 years, and indeed writing some of the earliest advice about walking in the area. Jean Edgecombe’s “Discovering Flinders Island”, “Flinders Island: The Furneaux Group” and “Flinders Island and Eastern Bass Strait”, while written from Sydney, is based on Edgecomb’s many visits and draws on both expert and islander knowledge extensively. Len Zell, in Wild Discovery Guides, prefaces the book with the comment “My visits to the island were brief and I was able to talk to only a few people”, although the guide does not suffer for this and it should not be considered a criticism. Rather, I make this point to indicate that temporary authors are the bulk of the authors, not that their work is in any way inferior for this.